Cricket is a bat-and-ball team sport that originated in England and is now played in more than 100 countries. A cricket match is contested by two teams, usually of eleven players each [1].

A cricket match is played on a grass field in the centre of which is a flat strip of ground 22 yards (20 m) long called a cricket pitch. A wicket, usually made of wood, is placed at each end of the pitch and used as a target.

The bowler, a player from the fielding team, bowls a hard leather, fist-sized, 5.5 ounces (160 g) cricket ball from the vicinity of one wicket towards the other, which is guarded by the batsman, a player from the opposing team. The ball usually bounces once before reaching the batsman. In defence of his wicket, the batsman plays the ball with a wooden cricket bat. Meanwhile, the other members of the bowler's team stand in various positions around the field as fielders, players who retrieve the ball in an effort to stop the batsman scoring runs, and if possible to get him or her out. The batsman — if he or she does not get out — may run between the wickets, exchanging ends with a second batsman (the "non-striker"), who has been stationed at the other end of the pitch. Each completed exchange of ends scores one run. Runs are also scored if the batsman hits the ball to the boundary of the playing area. The match is won by the team that scores more runs.

Cricket is essentially an outdoor sport, certainly at major level, and some games are played under floodlights. It cannot be played in poor weather due to the risk of accidents and so it is a seasonal sport. For example, it is played during the summer months in Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, while in the West Indies, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh it is played mostly during the winter months to escape the hurricane and monsoon seasons.

Governance rests primarily with the International Cricket Council (ICC), based in Dubai, which organises the sport worldwide via the domestic controlling bodies of the member countries. The ICC administers both men's and women's cricket, both versions being played at international level. Although men cannot play women's cricket, the rules do not disqualify women from playing in a men's team.

The rules are in the form of a code known as The Laws of Cricket [2] and these are maintained by the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), based in London, in consultation with the ICC and the domestic boards of control.

The game of cricket and its objectives

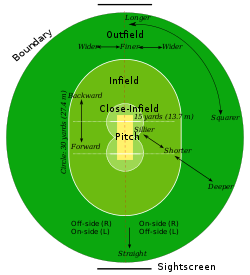

A cricket match is played between two teams (or sides) of eleven players each on a field of variable size and shape. The ground is grassy and is prepared by groundsmen whose jobs include fertilising, mowing, rolling and leveling the surface. Field diameters of 140–160 yards (130–150 m) are usual. The perimeter of the field is known as the boundary and this is sometimes painted and sometimes marked by a rope that encircles the outer edge of the field. The field may be round, square or oval – one of cricket's most famous venues is called The Oval.

In simple terms, the object of each team is to score more "runs" than the other team and so win the game. However, in certain types of cricket, it is also necessary to completely "dismiss" the other team in order to win the match which would otherwise be drawn.

Before play commences, the two team captains toss a coin to decide which team shall bat or bowl first. The captain who wins the toss makes his decision on the basis of tactical considerations which may include the current and expected pitch and weather conditions.

The key action takes place in a specially prepared area of the field (generally in the centre) that is called the "pitch". At either end of the pitch, 22 yards (20 m) apart, are placed the "wickets". These serve as a target for the "bowling" aka "fielding" side and are defended by the "batting" side which seeks to accumulate runs. Basically, a run is scored when the "batsman" has literally run the length of the pitch after hitting the ball with his bat, although as explained below there are many ways of scoring runs [3]. If the batsmen are not attempting to score any more runs, the ball is "dead" and is returned to the bowler to be bowled again [4].

The bowling side seeks to dismiss the batsmen by various means [5] until the batting side is "all out", whereupon the side that was bowling takes its turn to bat and the side that was batting must "take the field" [6].

In normal circumstances, there are 15 people on the field while a match is in play. Two of these are the "umpires" who regulate all on-field activity. Two are the batsmen, one of whom is the "striker" as he is facing the bowling; the other is called the "non-striker". The roles of the batsmen are interchangeable as runs are scored and "overs" are completed. The fielding side has all 11 players on the field together. One of them is the "bowler", another is the "wicketkeeper" and the other nine are called "fielders". The wicketkeeper (or keeper) is nearly always a specialist but any of the fielders can be called upon to bowl.

Pitch, wickets and creases

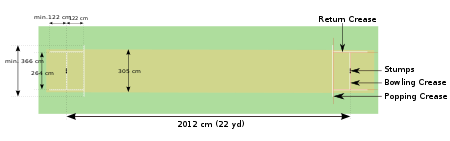

The pitch is 22 yards (20 m) long [7] between the wickets and is 10 feet (3.0 m) wide. It is a flat surface and has very short grass that tends to be worn away as the game progresses. The "condition" of the pitch has a significant bearing on the match and team tactics are always determined with the state of the pitch, both current and anticipated, as a deciding factor.

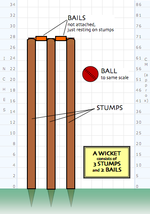

Each wicket consists of three wooden stumps placed in a straight line and surmounted by two wooden crosspieces called bails; the total height of the wicket including bails is 28.5 inches (720 mm) and the combined width of the three stumps is 9 inches (230 mm).

Four lines (aka creases) are painted onto the pitch around the wicket areas to define the batsman's "safe territory" and to determine the limit of the bowler's approach. These are called the "popping" (or batting) crease, the bowling crease and two "return" creases.

The stumps are placed in line on the bowling creases and so these must be 22 yards (20 m) apart. A bowling crease is 8 feet 8 inches (2.6 m) long with the middle stump placed dead centre. The popping crease has the same length, is parallel to the bowling crease and is 4 feet (1.2 m) in front of the wicket. The return creases are perpendicular to the other two; they are adjoined to the ends of the popping crease and are drawn through the ends of the bowling crease to a length of at least 8 feet (2.4 m).

When bowling the ball, the bowler's back foot in his "delivery stride" must land within the two return creases while his front foot must land on or behind the popping crease. If he breaks this rule, the umpire calls "No ball".

The batsman uses the popping crease at his end to stand when facing the bowler but it is more important to him that because it marks the limit of his safe territory and he can be stumped or run out (see Dismissals below) if the wicket is broken while he is "out of his ground".

Pitches vary in consistency, and thus in the amount of bounce, spin, and seam movement available to the bowler. Hard pitches are usually good to bat on because of high but even bounce. Dry pitches tend to deteriorate for batting as cracks often appear, and when this happens spinners can play a major role. Damp pitches, or pitches covered in grass (termed "green" pitches), allow good fast bowlers to extract extra bounce and seam movement. Such pitches tend to offer help to fast bowlers throughout the match, but become better for batting as the game goes on.

Bat and ball

The essence of the sport is that a bowler delivers the ball from his end of the pitch towards the batsman who, armed with a bat is "on strike" at the other end.

The bat is made of wood and takes the shape of a blade topped by a cylindrical handle. The blade must not be more than 4.25 inches (108 mm) wide and the total length of the bat not more than 38 inches (970 mm).

The bowler must employ an action in which the elbow does not straighten (within certain tolerance levels) to "bowl" the ball, which is a hard leather seamed spheroid projectile with a circumference limit of 9 inches (230 mm).

The hardness of the ball, which can be delivered at speeds of more than 90 miles per hour (140 km/h), is a matter for concern and batsmen wear protective clothing including "pads" (designed to protect the knees and shins), "batting gloves" for the hands, a helmet for the head and a "box" inside the trousers (for the more delicate part of the anatomy). Some batsmen wear additional padding inside their shirts and trousers such as thigh pads, arm pads, rib protectors and shoulder pads.

Umpires and scorers

The game on the field is regulated by two umpires, one of whom stands behind the wicket at the bowler's end, the other in a position called "square leg" which is several yards behind the batsman on strike. When the bowler delivers the ball, the umpire at the wicket is between the bowler and the non-striker. The umpires confer if there is doubt about playing conditions and can postpone the match by taking the players off the field if necessary: e.g., rain, deterioration of the light, crowd trouble.

Off the field and in televised matches, there is often a third umpire who can make decisions on certain incidents with the aid of video evidence. The third umpire is mandatory under the playing conditions for Test matches and limited overs internationals played between two ICC full members. These matches also have a match referee whose job is to ensure that play is within the Laws of cricket and the spirit of the game.

Off the field, the match details including runs and dismissals are recorded by two official scorers, one representing each team. The scorers are directed by the hand signals of an umpire. For example, the umpire raises a forefinger to signal that the batsman is out (has been dismissed); he raises both arms above his head if the batsman has hit the ball for six runs. The scorers are required by the Laws of cricket to record all runs scored, wickets taken and overs bowled. In practice they accumulate much additional data such as bowling analyses and run rates.

Unofficial scoring is carried on by spectators for their own benefit and by media scorers on behalf of broadcasters and newspapers.

Innings

The innings (always used in the plural form) is the term used for the collective performance of the batting side [8]. In theory, all eleven members of the batting side take a turn to bat but, for various reasons, an "innings" can end before they all do so (see below).

Depending on the type of match being played, each team has one or two innings apiece. The term "innings" is also sometimes used to describe an individual batsman's contribution ("he played a fine innings" etc).

The main aim of the bowler, supported by his fielders, is to dismiss the batsman. A batsman when dismissed is said to be "out" and that means he must leave the field of play and be replaced by the next batsman on his team. When ten batsmen have been dismissed (i.e., are out), then the whole team is dismissed and the innings is over. The last batsman, the one who has not been dismissed, is not allowed to continue alone as there must always be two batsmen "in". This batsman is termed "not out".

If an innings should end before ten batsmen have been dismissed, there are two "not out" batsmen. An innings can end early because the batting side's captain has chosen to "declare" the innings closed, which is a tactical decision; or because the batting side has achieved its target and won the game; or because the game has ended prematurely due to bad weather or running out of time. In limited overs cricket, there might be two batsmen still "in" when the last of the allotted overs has been bowled.

Overs

The bowler bowls the ball in sets of six deliveries (or "balls") and each set of six balls is called an over. This name came about because the umpire calls "Over!" when six balls have been bowled. At this point, another bowler is deployed at the other end and the fielding side changes ends. A bowler cannot bowl two successive overs, although a bowler can bowl unchanged at the same end for several overs. The batsmen do not change ends and so the one who was non-striker is now the striker and vice-versa. The umpires also change positions so that the one who was at square leg now stands behind the wicket at the non-striker's end and vice-versa.

Team structure

A team consists of eleven players. Depending on his or her primary skills, a player may be classified as a specialist batsman or bowler. A well-balanced team usually has five or six specialist batsmen and four or five specialist bowlers. Teams nearly always include a specialist wicket-keeper because of the importance of this fielding position. Each team is headed by a captain who is responsible for making tactical decisions such as determining the batting order, the placement of fielders and the rotation of bowlers.

A player who excels in both batting and bowling is known as an all-rounder. One who excels as a batsman and wicket-keeper is known as a "wicket-keeper/batsman", sometimes regarded as a type of all-rounder. True all-rounders are rare as most players focus on either batting or bowling skills.

Fielding

All eleven players on the fielding side take the field together.

One of them is the wicket-keeper aka "keeper" who operates behind the wicket being defended by the batsman on strike. Wicket-keeping is normally a specialist occupation and his primary job is to gather deliveries that the batsman does not hit, so that the batsmen cannot run byes. He wears special gloves (he is the only fielder allowed to do so), and pads to cover his lower legs. Owing to his position directly behind the striker, the wicket-keeper has a good chance of getting a batsman out caught off a fine edge from the bat. He is the only player who can get a batsman out stumped.

Apart from the one currently bowling, the other nine fielders are tactically deployed by the team captain in chosen positions around the field. These positions are not fixed but they are known by specific and sometimes colourful names such as "slip", "third man", "silly mid on" and "long leg". There are always many unprotected areas.

The captain is the most important member of the fielding side as he determines all the tactics including who should bowl (and how); and he is responsible for "setting the field", though usually in consultation with the bowler.

In all forms of cricket, if a fielder gets injured or becomes ill during a match, a substitute is allowed to field instead of him. The substitute cannot bowl, act as a captain or keep wicket. The substitute leaves the field when the injured player is fit to return.

Bowling

The bowler reaches his delivery stride by means of a "run-up", although some bowlers with a very slow delivery take no more than a couple of steps before bowling. A fast bowler needs momentum and takes quite a long run-up, running very fast as he does so.

The fastest bowlers can deliver the ball at a speed of over 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) and they sometimes rely on sheer speed to try and defeat the batsman, who is forced to react very quickly to a ball that reaches him in an instant.

Other fast bowlers rely on a mixture of speed and guile. Some fast bowlers make use of the seam of the ball so that it "curves" or "swings" in flight and this type of delivery can deceive a batsman into mistiming his shot so that the ball touches the edge of the bat and can then be "caught behind" by the wicketkeeper or a slip fielder.

At the other end of the bowling scale is the "spinner" who bowls at a relatively slow pace and relies entirely on guile to deceive the batsman. A spinner will often "buy his wicket" by "tossing one up" to lure the batsman into making an adventurous shot. The batsman has to be very wary of such deliveries as they are often "flighted" or spun so that the ball will not behave quite as he expects and he could be "trapped" into getting himself out.

In between the pacemen and the spinners are the "medium pacers" who rely on persistent accuracy to try and contain the rate of scoring and wear down the batsman's concentration.

All bowlers are classified according to their pace or style. The classifications, as with much cricket terminology, can be very confusing. Hence, a bowler could be classified as LF, meaning he is a left arm fast bowler; or as LBG, meaning he is a right arm spin bowler who bowls deliveries that are called a "leg break" and a "googly"!

During the bowling action the elbow may be held at any angle and may bend further, but may not straighten out. If the elbow straightens illegally then the square-leg umpire may call no-ball. The current laws allow a bowler to straighten his arm 15 degrees or less.

Batting

At any one time, there are two batsmen in the playing area. One takes station at the striker's end to defend the wicket as above and to score runs if possible. His partner, the non-striker, is at the end where the bowler is operating.

Batsmen come in to bat in a batting order, decided by the team captain. The first two batsmen - the "openers" - usually face the most hostile bowling, from fresh fast bowlers with a new ball. The top batting positions are usually given to the most competent batsmen in the team, and the non-batsmen typically bat last. The pre-announced batting order is not mandatory and when a wicket falls any player who has not yet batted may be sent in next.

If a batsman "retires" (usually due to injury) and cannot return, he is actually "not out" and his retirement does not count as a dismissal, though in effect he has been dismissed because his innings is over. Substitute batsmen are not allowed, although substitute fielders are.

A skilled batsman can use a wide array of "shots" or "strokes" in both defensive and attacking mode. The idea is to hit the ball to best effect with the flat surface of the bat's blade. If the ball touches the side of the bat it is called an "edge". Batsmen do not always seek to hit the ball as hard as possible and a good player can score runs just by making a deft stroke with a turn of the wrists or by simply "blocking" the ball but directing it away from fielders so that he has time to take a run.

There is a wide variety of shots played in cricket. The batsman's repertoire includes strokes named according to the style of swing and the direction aimed: e.g., "cut", "drive", "hook", "pull", etc.

Note that a batsman does not have to play a shot and can "leave" the ball to go through to the wicketkeeper, providing he thinks it will not hit his wicket. Equally, he does not have to attempt a run when he hits the ball with his bat. He can deliberately use his leg to block the ball and thereby "pad it away" but this is risky because of the lbw rule.

In the event of an injured batsman being fit to bat but not to run, the umpires and the fielding captain may allow another member of the batting side to be a runner. If possible, the runner must already have batted. The runner's only task is to run between the wickets instead of the injured batsman. The runner is required to wear and carry exactly the same equipment as the incapacitated batsman. It is possible for both batsmen to have runners.

Runs

The primary concern of the batsman on strike (i.e., the "striker") is to prevent the ball hitting the wicket and secondarily to score runs by hitting the ball with his bat so that he and his partner have time to run from one end of the pitch to the other before the fielding side can return the ball. To register a run, both runners must touch the ground behind the crease with either their bats or their bodies (the batsmen carry their bats as they run). Each completed run increments the score.

More than one run can be scored from a single hit but, while hits worth one to three runs are common, the size of the field is such that it is usually difficult to run four or more. To compensate for this, hits that reach the boundary of the field are automatically awarded four runs if the ball touches the ground en route to the boundary or six runs if the ball clears the boundary on the full. The batsmen do not need to run if the ball reaches or crosses the boundary.

Hits for five are unusual and generally rely on the help of "overthrows" by a fielder returning the ball. If an odd number of runs is scored by the striker, the two batsmen have changed ends and the one who was non-striker is now the striker. Only the striker can score individual runs but all runs are added to the team's total.

The decision to attempt a run is ideally made by the batsman who has the better view of the ball's progress and this is communicated by calling: "yes", "no" and "wait" are often heard.

Running is a calculated risk because if a fielder breaks the wicket with the ball while no part of the batsman or his bat is grounded behind the popping crease, the batsman nearest the broken wicket is run out.

A team's score is reported in terms of the number of runs scored and the number of batsmen that have been dismissed. For example, if five batsmen are out and the team has scored 224 runs, they are said to have scored 224 for the loss of 5 wickets (commonly shortened to "224 for five" and written 224/5 or, in Australia, "five for 224" and 5/224).

Extras

Additional runs can be gained by the batting team as extras (called "sundries" in Australia) by courtesy of the fielding side. This is achieved in four ways:

- No ball – a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he breaks the rules of bowling either by (a) using an inappropriate arm action; (b) overstepping the popping crease; (c) having a foot outside the return crease

- Wide – a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he bowls so that the ball is out of the batsman's reach

- Bye – extra(s) awarded if the batsman misses the ball and it goes past the wicketkeeper to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way (note that the mark of a good wicketkeeper is one who restricts the tally of byes to a minimum)

- Leg bye – extra(s) awarded if the ball hits the batsman's body, but not his bat, and it goes away from the fielders to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way.

When the bowler has bowled a no ball or a wide, his team incurs an additional penalty because that ball (i.e., delivery) has to be bowled again and hence the batting side has the opportunity to score more runs from this extra ball.

The batsmen have to run (i.e., unless the ball goes to the boundary for four) to claim byes and leg byes but these only count towards the team total, not to the striker's individual total for which runs must be scored off the bat.

No comments:

Post a Comment